Ulysses S. Grant

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

This article is about the president of the United States. For others with the same name, see Ulysses S. Grant (disambiguation).

"General Grant" redirects here. For other uses, see General Grant (disambiguation).

| General of the Army Ulysses S. Grant |

|

|---|---|

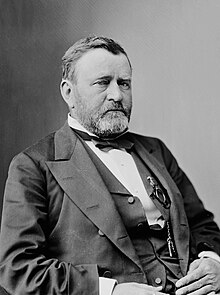

Grant during the mid-1870s

|

|

| 18th President of the United States | |

| In office March 4, 1869 – March 4, 1877 |

|

| Vice President |

|

| Preceded by | Andrew Johnson |

| Succeeded by | Rutherford B. Hayes |

| 6th Commanding General of the United States Army | |

| In office March 9, 1864 – March 4, 1869 |

|

| President | |

| Preceded by | Henry W. Halleck |

| Succeeded by | William Tecumseh Sherman |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Hiram Ulysses Grant April 27, 1822 Point Pleasant, Ohio, U.S. |

| Died | July 23, 1885 (aged 63) Wilton, New York, U.S. |

| Resting place | General Grant National Memorial Manhattan, New York |

| Political party | |

| Spouse(s) | Julia Dent (m. 1848) |

| Children | Frederick, Ulysses Jr., Nellie, and Jesse |

| Alma mater | United States Military Academy |

| Occupation | soldier, politician |

| Religion | Nondenominational Protestant |

| Signature | |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/branch | Union Army |

| Years of service | 1839–1854 1861–1869 |

| Rank | |

| Commands |

|

| Battles/wars | Mexican–American War American Civil War |

|

||

|---|---|---|

|

President of the United States Post-Presidency |

||

Grant graduated in 1843 from the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, served in the Mexican–American War and initially retired in 1854. He struggled financially in civilian life. When the Civil War began in 1861, he rejoined the U.S. Army. In 1862, Grant took control of Kentucky and most of Tennessee, and led Union forces to victory in the Battle of Shiloh, earning a reputation as an aggressive commander. He incorporated displaced African American slaves into the Union war effort. In July 1863, after a series of coordinated battles, Grant defeated Confederate armies and seized Vicksburg, giving the Union control of the Mississippi River and dividing the Confederacy in two. After his victories in the Chattanooga Campaign, Lincoln promoted him to lieutenant-general and Commanding General of the United States Army in March 1864. Grant confronted Robert E. Lee in a series of bloody battles, trapping Lee's army in their defense of Richmond. Grant coordinated a series of devastating campaigns in other theaters. In April 1865, Lee surrendered to Grant at Appomattox, effectively ending the war. Historians have hailed Grant's military genius, and his strategies are featured in military history textbooks, but a minority contend that he won by brute force rather than superior strategy.[1]

After the Civil War, Grant led the army's supervision of Reconstruction in the former Confederate states. Elected president in 1868 and reelected in 1872, Grant stabilized the nation during the turbulent Reconstruction period, prosecuted the Ku Klux Klan, and enforced civil and voting rights laws using the army and the Department of Justice. He used the army to build the Republican Party in the South, based on black voters, Northern newcomers ("carpetbaggers"), and native Southern white supporters ("scalawags"). After the disenfranchisement of some former Confederates, Republicans gained majorities and African Americans were elected to Congress and high state offices. In his second term, the Republican coalitions in the South splintered and were defeated one by one as redeemers (conservative whites) regained control using coercion and violence. Grant's Indian peace policy initially reduced frontier violence, but is best known for the Great Sioux War of 1876, where George Custer and his regiment were killed at the Battle of the Little Bighorn. Grant responded to charges of corruption in executive offices more than any other 19th Century president. He appointed the first Civil Service Commission and signed legislation ending the corrupt moiety system.

In foreign policy, Grant sought to increase American trade and influence, while remaining at peace with the world. His administration successfully resolved the Alabama Claims by the Treaty of Washington with Great Britain, ending wartime tensions. Grant avoided war with Spain over the Virginius Affair, but Congress rejected his attempted annexation of the Dominican Republic. In trade policy, Grant's administration implemented a gold standard and sought to strengthen the dollar. Corruption charges escalated during his second term, while his response to the Panic of 1873 proved ineffective nationally in halting the five-year industrial depression that produced high unemployment, low prices, low profits, and bankruptcies. Grant left office in 1877 and embarked on a two-year world tour which greatly helped to establish the United States' presence abroad and captured the nation's attention.

In 1880, Grant was unsuccessful in obtaining a Republican presidential nomination for a third term. Facing severe investment reversals and dying of throat cancer, he completed his memoirs, which proved to be a major literary work and financial success. His death in 1885 prompted an outpouring in support of national unity. Historical assessment of Grant's legacy has varied considerably over the years. Early historical evaluations were negative about Grant's presidency, often focusing on the corruption charges against his associates. This trend began to change in the later 20th century. Scholars in general rank his presidency below the average, but modern research, in part focusing on civil rights, evaluates his administration more positively.

Contents

Early life

Further information: Early life and career of Ulysses S. Grant

Grant's birthplace in Point Pleasant, Ohio

Early military career and personal life

Second lieutenant Ulysses S. Grant in full dress uniform in 1843

West Point and first assignment

When a cadet opening became available in March 1839, Congressman Thomas L. Hamer nominated the 16-year-old Grant to the United States Military Academy (USMA) at West Point, New York.[12] Grant entered the school on the Hudson River in May, and would be trained there for next four years.[13] Hamer mistakenly wrote down the name as "Ulysses S. Grant of Ohio", and this became his adopted name.[b][14] His nickname became "Sam" among army colleagues at the academy since the initials "U.S." also stood for "Uncle Sam". As he later recalled it, "a military life had no charms for me"; he was lax in his studies, but he achieved above-average grades in mathematics and geology.[15] Quiet by nature, he established a few intimate friends, including Frederick Tracy Dent and Rufus Ingalls.[16] Grant developed a reputation as a fearless and expert horseman known as a horse whisperer, setting an equestrian high-jump record that stood for almost 25 years.[17] He also studied under Romantic artist Robert Walter Weir and produced nine surviving artworks. He graduated in 1843, ranking 21st in a class of 39. Glad to leave the academy, his plan was to resign his commission after his four-year term of duty.[18] Despite his excellent horsemanship, he was not assigned to the cavalry (assignments were determined by class rank, not aptitude), but to the 4th Infantry Regiment. He was made regimental quartermaster, managing supplies and equipment, with the rank of brevet second lieutenant.[19]Grant's first assignment after graduation took him to the Jefferson Barracks near St. Louis, Missouri.[20] Commanded by Colonel Stephen W. Kearny, the Barracks was the nation's largest military base in the west.[21] Grant was happy with his new commander, but looked forward to the end of his military service and a possible teaching career.[22] He spent some of his time in Missouri visiting the family of his West Point classmate, Frederick Tracy Dent; he became engaged to Dent's sister, Julia, in 1844.[22] Four years later they married on August 22, 1848.[23] Over time, they had four children: Frederick, Ulysses Jr. ("Buck"), Ellen ("Nellie"), and Jesse.[24]

Mexican American War

Amid rising tensions with Mexico following the United States' annexation of Texas, President John Tyler ordered Grant's unit to Louisiana as part of the Army of Observation under Major General Zachary Taylor.[25] When the Mexican–American War broke out, President James K. Polk directed the U.S. Army to invade Mexico in 1846.[26] Although a quartermaster, Grant led a cavalry charge at the Battle of Resaca de la Palma.[27] At Monterrey he demonstrated his equestrian ability, by volunteering to carry a dispatch through sniper-lined streets while hanging off the side of his horse, keeping the animal between him and the enemy.[28] Polk, wary of Taylor's growing popularity, divided his forces, sending some troops (including Grant's unit) to form a new army under Major General Winfield Scott.[29] Traveling with a naval fleet, Scott's army landed at Veracruz and advanced toward Mexico City.[30] The army met the Mexican forces at the battles of Molino del Rey and Chapultepec outside Mexico City.[31] Grant was a quartermaster in charge of supplies and did not have a combat role, but he yearned for one and finally was allowed to take part in dangerous missions.[32] At San Cosmé, men under Grant's direction dragged a disassembled howitzer into a church steeple, reassembled it, and bombarded nearby Mexican troops.[31] His bravery and initiative earned him brevet promotions; he became a temporary captain while his permanent rank was lieutenant.[33] On September 14, 1847, Scott's army, including Grant, marched into the city, and the Mexicans agreed to peace soon afterward.[34]During this war Grant studied the tactics and strategies of Scott and others, often second guessing their moves beforehand.[35] In his Memoirs, he wrote that this is how he learned about military leadership, and in retrospect identified his leadership style with Taylor's. Even so, he believed that the Mexican War was wrongful and that the territorial gains from the war were designed to expand slavery. Grant reflected in 1883, "I was bitterly opposed to the measure, and to this day, regard the war, which resulted, as one of the most unjust ever waged by a stronger against a weaker nation." He opined that the Civil War was punishment inflicted on the nation for its aggression in Mexico.[36]

Pacific west and resignation

Grant's mandatory service expired during the war, but he chose to remain a soldier. Grant's first post-war assignments took him and Julia to Detroit and then to Sackets Harbor, New York.[37] In 1852, Grant was ordered to the Pacific Northwest; the army was stationed there to keep peace between settlers and Indians after the Cayuse War, and to protect the West Coast. Julia, who was eight months pregnant with Ulysses Jr., did not accompany him.[38] While traveling overland through Panama, an outbreak of cholera among his fellow travelers caused 150 fatalities; Grant arranged makeshift transportation and hospital facilities to care for the sick.[39] Grant debarked in San Francisco during the height of the California Gold Rush.[38][40] His next assignment sent him north to Fort Vancouver in the Oregon Territory (subsequently Washington Territory in March 1853). To supplement a military salary which was inadequate to support his family, Grant tried and failed at several business ventures, confirming Jesse Grant's belief that his son had no head for business.[41] Promoted to captain in the summer of 1853, Grant was assigned in February 1854 to command Company F, 4th Infantry, at Fort Humboldt in California.[42] He was unhappy being separated from his family, and rumors circulated that he was drinking to excess. The commanding officer at Fort Humboldt, Lieutenant Colonel Robert C. Buchanan, received reports that Grant became intoxicated off-duty while seated at the pay officer's table. In lieu of a court-martial, Buchanan gave Grant an ultimatum to resign; he did so, effective July 31, 1854, without explanation.[43] The War Department stated on his record, "Nothing stands against his good name."[44] Historians overwhelmingly agree that his drunkenness at the time was a fact, though there are no eyewitness reports extant.[45] After Grant's retirement, rumors persisted in the regular army of his drinking.[45] Years later, he said, "the vice of intemperance (drunkenness) had not a little to do with my decision to resign."[46] Grant returned to St. Louis, uncertain about his future, but reunited with his family.[47]Civilian struggles and politics

"Hardscrabble", the home Grant built in Missouri for his family

Having met with no success farming, the Grants left the farm when their fourth and final child was born in 1858. The following year in 1859 Grant freed his only slave Jones, who was 35 years old and worth about $1,500, instead of selling him at a time when Grant desperately needed money.[50][52] For the next year, the family took a small house in St. Louis where he worked with Julia's cousin Harry Boggs as a bill collector, again without success.[53] In 1860, Jesse offered him the job in Galena without conditions, and Grant accepted. The leather shop, "Grant & Perkins", sold harnesses, saddles, and other leather goods, and purchased hides from farmers in the prosperous Galena area. Grant and family moved to a rental house that year.[54]

After Grant had retired from the military, many considered him allied politically to Julia's father, Frederick Dent, a prominent Missouri Democrat.[55] In the 1856 election, Grant cast his first presidential vote for the Democrat, James Buchanan, later saying he was really voting against John C. Frémont, the first Republican candidate, over concern that Frémont's anti-slavery position would motivate southern states to secede.[56] In 1859, Grant's vote for Buchanan and his political affiliation to his father-in-law cost him an appointment to become county engineer.[55] Grant's own father in Illinois, Jesse, was an outspoken Republican in Galena.[57] In 1860, Grant was an open Democrat, favoring Democrat Stephen A. Douglas over Abraham Lincoln, and Lincoln over the Southern Democrat, John C. Breckinridge. Lacking the residency requirements in Illinois at the time, he could not vote.[56][55] Grant opposed the southern states' secession at the outbreak of the Civil War and remained loyal to the Union.[55]

Civil War

Main article: Ulysses S. Grant and the American Civil War

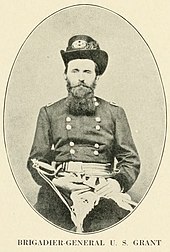

Brig. Gen. Grant in 1861

Without any formal rank in the army, Grant helped recruit a company of volunteers and accompanied them to Springfield, the state capital.[61] During this time, Grant quickly perceived that the war would be fought for the most part by volunteers and not career soldiers.[62] Illinois' Governor Richard Yates offered Grant a militia commission to recruit and train volunteer units, which he accepted, but he still wanted a field command in the army. He made several efforts through his professional contacts, including Major General George B. McClellan. McClellan refused to meet him, remembering Grant's earlier reputation for drinking while stationed in California.[63] Meanwhile, Grant continued serving at the training camps and made a positive impression on the volunteer Union recruits.[64]

With the aid of his advocate in Washington, Illinois congressman Elihu B. Washburne, Grant was formally promoted to Colonel on June 14, 1861, and put in charge of disciplining the unruly 21st Illinois Volunteer Infantry Regiment. To restore discipline, Grant had one troublemaker bound and gagged to a post for being drunk and disorderly.[65] Transferred to northern Missouri, Grant was promoted by Lincoln to Brigadier General, backdated to May 17, 1861, again with Washburne's support.[66] Believing Grant was a general of "dogged persistence" and "iron will", Major General John C. Frémont assigned Grant command of troops near Cairo, Illinois, by the end of August 1861.[67] Under Frémont's authority Grant advanced into Paducah and took the town without a fight.[68]

Belmont, Forts Henry and Donelson

Battle of Fort Donelson

Emboldened by Lincoln's call for a general advance of all Union forces, Grant ordered an immediate assault on nearby Fort Donelson, which dominated the Cumberland River (this time without Halleck's permission). On February 15, Grant and Foote met stiff resistance from Confederate forces under Pillow. Reinforced by 10,000 troops, Grant's army totaled 25,000 troops against 12,000 Confederates. Foote's first approach was repulsed, and the Confederates attempted a breakout, pushing Grant's right flank into disorganized retreat.[72] Grant rallied his troops, resumed the offensive, retook the Union right, and attacked Pillow's left. Pillow ordered Confederate troops back into the fort and relinquished command to Brigadier General Simon Bolivar Buckner, who the next day acceded to Grant's demand for his "unconditional and immediate surrender." Lincoln promoted Grant to major-general of volunteers while the Northern press treated Grant as a hero. Playing off his initials, they took to calling him "Unconditional Surrender Grant".[73]

Shiloh and aftermath

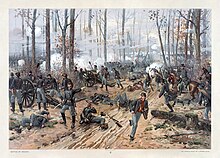

The Battle of Shiloh

Further information: Battle of Shiloh

Encamped on the western bank of the Tennessee River, Grant's Army of the Tennessee, now numbering about 45,000 troops, prepared to attack a Confederate army of roughly equal strength at Corinth, Mississippi, a vital railroad junction. The Confederates, led by Generals Albert Sidney Johnston and P.G.T. Beauregard,

struck first on April 6, 1862, attacking five divisions of Grant's army

bivouacked at Pittsburg Landing, not far from the Shiloh meetinghouse.[74] Grant's troops were not entrenched and were taken by surprise, falling back before the Confederate onslaught.[75] At day's end, the Confederates captured one Union division, but Grant's army was able to hold the Landing.[76]

The remaining Union army might have been destroyed, but the

Confederates halted due to exhaustion, confusion, and a lack of

reinforcements.[77] Grant, bolstered by 18,000 fresh troops from the divisions of Major Generals Don Carlos Buell and Lew Wallace, counterattacked at dawn the next day [78] The Northerners regained the field and forced the rebels to retreat back to Corinth.[79]In Shiloh's aftermath, the Northern press criticized Grant for high casualties and for his alleged drunkenness during the battle.[80] Shiloh was the costliest battle in American history to that point, with total casualties of about 23,800.[81] Halleck arrived at Pittsburg Landing on April 9, and removed Grant from field command, proceeding to capture Corinth. Discouraged and disappointed, Grant considered resigning his commission, but Brigadier General William Tecumseh Sherman, one of his division commanders, convinced him to stay.[82] Lincoln overruled Grant's critics, saying "I can't spare this man; he fights." Ordered to Washington, Halleck on July 11 reinstated Grant as field commander of the Army of the Tennessee.[83] On September 19, Grant's army defeated Confederates at the Battle of Iuka, then successfully defended Corinth, inflicting heavy casualties on the enemy.[84] On October 25, Grant assumed command of the District of the Tennessee.[85] In November, after Lincoln's preliminary Emancipation Proclamation, Grant ordered units under his command, headed by Chaplain John Eaton, to incorporate contraband slaves into the Union war effort, giving them clothes, shelter, and wages for their services.[86]

Vicksburg campaign

Further information: Vicksburg Campaign and General Order No. 11 (1862)

The Battle of Jackson, fought on May 14, 1863, was part of the Vicksburg Campaign.

Along with his military responsibilities in the months following Grant's return to command, he was concerned over an expanding illicit cotton trade in his district.[93] He believed the trade undermined the Union war effort, funded the Confederacy, and prolonged the war, while Union soldiers died in the fields.[94] On December 17, he issued General Order No. 11, expelling "Jews, as a class," from the district, saying that Jewish merchants were violating trade regulations.[95] Writing in 2012, historian Jonathan D. Sarna said Grant "issued the most notorious anti-Jewish official order in American history."[96] Historians' opinions vary on Grant's motives for issuing the order.[97] Jewish leaders complained to Lincoln while the Northern press criticized Grant.[98] Lincoln demanded the order be revoked and Grant rescinded it within three weeks.[99] When interviewed years after the war, in response to accusations of his General Order being anti-Jewish, Grant explained: "During war times these nice distinctions were disregarded, we had no time to handle things with kid gloves."[100] Grant made amends with the Jewish community during his presidency.[101]

On January 29, 1863, Grant assumed personal overall command and during the months of February and March made a series of attempts to advance his army through water-logged terrain to bypass Vicksburg's guns; these also proved ineffective, however, Union soldiers became better trained.[102] On April 16, 1863, Grant ordered Admiral David Porter's Union gunboats south under fire from the Vicksburg batteries to meet up with his Union troops who had marched south down the west side of the Mississippi River.[103] Grant ordered diversionary battles, confusing Pemberton and allowing Grant's army to cross east over the Mississippi, landing troops at Bruinsburg.[104] Continuing eastward, Grant's army captured Port Gibson, Raymond, and Jackson, the state capital and Confederate railroad supply center. Advancing his army to Vicksburg, Grant defeated Pemberton's army at the Battle of Champion Hill on May 16, forcing Pemberton to retreat into Vicksburg.[105] After Grant's men assaulted the Vicksburg entrenchments twice, suffering severe losses, they settled in for a siege lasting seven weeks. Pemberton surrendered Vicksburg to Grant on July 4, 1863.[106]

The fall of Vicksburg gave Union forces control over the Mississippi River and split the Confederacy in two. By that time, Grant's political sympathies fully coincided with the Radical Republicans' aggressive prosecution of the war and emancipation of the slaves.[107] Although the success at Vicksburg was a great morale boost for the Union war effort, Grant received criticism for his decisions and his alleged drunkenness.[108] The personal rivalry between McClernand and Grant continued after Vicksburg, until Grant removed McClernand from command when he contravened Grant by publishing an order without permission.[109] When Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton suggested Grant be brought back east to run the Army of the Potomac, Grant demurred, writing that he knew the geography and resources of the West better and he did not want to upset the chain of command in the East.[110]

Chattanooga and promotion

Further information: Chattanooga Campaign

Union troops swarm Missionary Ridge and defeat Bragg's army.

On March 3, 1864, Lincoln promoted Grant to lieutenant general, giving him command of all Union Armies, answering only to the President.[122] Grant assigned Sherman the Division of the Mississippi and traveled east to Washington D.C., meeting with Lincoln to devise a strategy of total war against the Confederacy. After settling Julia into a house in Georgetown, Grant established his headquarters with General George Meade's Army of the Potomac in Culpeper, Virginia.[123] He devised a strategy of coordinated Union offensives, attacking the rebel armies at the same time to keep the Confederates from shifting reinforcements within their interior lines. Sherman was to pursue Joseph E. Johnston's Army of Tennessee, while Meade would lead the Army of the Potomac, with Grant in camp, to attack Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia.[124] Major General Benjamin Butler was to advance towards Richmond from the south, up the James River.[125] If Lee was forced south as expected, Grant would join forces with Butler's armies and be fed supplies from the James. Major General Franz Sigel was to capture the railroad line at Lynchburg, move east, and attack from the Blue Ridge Mountains.[126] Grant knew that Lee had limited manpower and that a war of attrition fought on a battlefield without entrenchments would lead to Lee's defeat.[127]

Grant was now riding a rising tide of popularity, and there was talk that a Union victory early in the year could lead to his candidacy for the presidency. Grant was aware of the rumors, but had ruled out a political candidacy; the possibility would soon vanish with delays on the battlefield.[127]

Overland Campaign and Union victory

Further information: Overland Campaign

The Battle of the Wilderness began almost a year of bloody fighting between forces commanded by Grant and Lee

Lee surrendering to Grant at McLean House. Those depicted also include Custer, Babcock, Sheridan, Rawlins, Meade, and Parker.

Commanding General Grant at the Battle of Cold Harbor in 1864

At Petersberg, Grant approved of a plan to blow up part of the enemy trenches from an underground tunnel. The explosion created a crater, into which poorly-led Union troops poured. Recovering from the surprise, Confederates surrounded the crater and easily picked off Union troops within it. The Union's 3500 casualties outnumbered the Confederates' by three-to-one; although the plan could have been successful if implemented correctly, Grant admitted the tactic had been a "stupendous failure".[133] On August 9, 1864, Grant, who had just arrived at his headquarters in City Point, narrowly escaped death when Confederate spies blew up an ammunition barge in the James River.[134] Rather than fight Lee in a full frontal attack as he had done at Cold Harbor, Grant continued to extend Lee's defenses south and west of Petersburg, to capture vital railroad links.[135] As Grant continued to push the Union advance westward, Lee's lines became overstretched and undermanned. After the Federal army rebuilt the City Point Railroad, Grant was able to use mortars to attack Lee's entrenchments.[136] On September 2, Sherman captured Atlanta while Confederate forces retreated, ensuring Lincoln's reelection in November.[137] Sherman convinced Grant and Lincoln to send his army to march on Savannah devastating the Confederate heartland.[138]

Once Sherman reached the East Coast and Thomas dispatched John Bell Hood's forces in Tennessee, Union victory appeared certain, and Lincoln attempted negotiations. He enlisted Francis Preston Blair to carry a message to Confederate President Jefferson Davis. Davis and Lincoln each appointed commissioners, but the conference soon stalled. Grant contacted Lincoln, who agreed to personally meet with the commissioners at Fort Monroe. The peace conference that took place near Union-controlled Fort Monroe was ultimately fruitless, but represented Grant's first foray into diplomacy.[139]

Grant (center left) next to Lincoln with General Sherman (far left) and Admiral Porter (right) — The Peacemakers

Lincoln's assassination

Main article: Assassination of Abraham Lincoln

On April 14, five days after Grant's victory at Appomattox, he

attended a cabinet meeting in Washington. Lincoln invited him and his

wife to Ford's Theater,

but they declined as they had plans to travel to Philadelphia. In a

conspiracy that targeted several government leaders, Lincoln was fatally

shot by John Wilkes Booth at the theater, and died the next morning.[144] Many, including Grant himself, thought that he had been a target in the plot.[145]

Secretary of War Stanton notified him of the President's death and

summoned him back to Washington. Attending Lincoln's funeral on April

19, Grant stood alone and wept openly; he later said Lincoln was "the

greatest man I have ever known."[146] Regarding the new President, Andrew Johnson,

Grant told Julia that he dreaded the change in administrations; he

judged Johnson's attitude toward white southerners as one that would

"make them unwilling citizens", and initially thought that with

President Johnson, "Reconstruction has been set back no telling how

far."[147]Commanding General

Main article: Ulysses S. Grant as commanding general, 1865–1869

Beginning Reconstruction

The post-Civil War home of Ulysses S. Grant, in Galena, Illinois

In November 1865, President Andrew Johnson sent Grant on a fact-finding mission to the South. Afterwards, Grant recommended continuation of a reformed Freedmen's Bureau, which Johnson opposed, but advised against the use of black troops in garrisons, which he believed encouraged an alternative to farm labor.[151] Grant did not believe the people of the devastated South were ready for civilian self-rule, and that both whites and blacks in the South required protection by the federal government.[152] He also warned of threats by disaffected poor people, black and white, and recommended that local decision-making be entrusted only to "thinking men of the South" (i.e., white men of property).[153] In this respect, Grant's opinion on Reconstruction aligned with Johnson's policy of pardoning established southern leaders and restoring them to their positions of power.[154] He joined Johnson in arguing that Congress should allow representatives from the South to take their seats.[155] On July 25, 1866, Congress promoted Grant to the newly created rank of General of the Army of the United States.[156]

Breach with Johnson

Clockwise from lower left: Graduated at West Point 1843; Chapultepec

1847; Drilling his Volunteers 1861; Fort Donelson 1862; Shiloh 1862;

Vicksburg 1863; Chattanooga 1863; Commander-in-Chief 1864; Lee's

Surrender 1865

Conflict between radicals and conservatives continued after the 1866 congressional elections. Rejecting Johnson's vision for quick reconciliation with former Confederates, Congress passed the Reconstruction Acts, which divided the southern states into five military districts to protect the freedman's constitutional and congressional rights. Military district governors were to lead transitional state governments in each district. Grant, who was to select the general to govern each district from a group designated by Johnson, preferred Congress's plan for enforcement of Reconstruction.[162] Grant was optimistic that Reconstruction Acts would help pacify the South.[163] By complying with the Acts and instructing his subordinates to do likewise, Grant further alienated Johnson. When Sheridan removed public officials in Louisiana who impeded Reconstruction, Johnson was displeased and sought Sheridan's removal.[164] Grant recommended a rebuke, but not a dismissal.[165] Throughout the Reconstruction period, Grant and the military protected the rights of more than 1,500 African Americans elected to political office.[166] In 1866, Congress renewed the Freedmen's Bureau over Johnson's vetoes and with Grant's support, and passed the first Civil Rights Act protecting African American civil rights by nullifying black codes.[167] On July 19, 1867, Congress, again over Johnson's veto, passed a measure that authorized Grant to have oversight in enforcing congressional Reconstruction, making Southern state governments subordinate to military control.[168]

Johnson's impeachment

Johnson wished to replace Stanton, a Lincoln appointee who sympathized with Congressional Reconstruction. To keep Grant under control as a potential political rival, Johnson asked him to take the post. Grant recommended against the move, in light of the Tenure of Office Act, which required Senate approval for cabinet removals. Johnson believed the Act did not apply to officers appointed by the previous president, and forced the issue by making Grant an interim appointee during a Senate recess. Grant agreed to accept the post temporarily, and Stanton vacated the office until the Senate reconvened.[169]When the Senate reinstated Stanton, Johnson told Grant to refuse to surrender the office and let the courts resolve the matter. Grant told Johnson in private that violating the Tenure of Office Act was a federal offense, which could result in a fine or imprisonment. Believing he had no other legal alternatives, Grant returned the office to Stanton. This incurred Johnson's wrath; at a cabinet meeting immediately afterward, Johnson accused Grant of breaking his promise to remain Secretary of War. Grant disputed that he had ever made such a promise although cabinet members later testified he had done so.[170] Newspapers friendly to Johnson published a series of articles to discredit Grant over returning the War Department to Stanton, stating that Grant had been deceptive in the matter.[170] This public insult infuriated Grant, and he defended himself in an angry letter to Johnson, after which the two men were confirmed foes. When Grant's statement became public, it increased his popularity among Radical Republicans and he emerged from the controversy unscathed.[170] Although Grant favored Johnson's impeachment, he took no active role in the impeachment proceedings against Johnson, which were fueled in part by Johnson's removal of Stanton. Johnson barely survived, and none of the other Republican leaders directly involved benefited politically in their unsuccessful attempt to remove the president.[171]

Election of 1868

First inauguration of Ulysses S. Grant on the steps of the Capitol on March 4, 1869

Main article: United States presidential election, 1868

While remaining Commanding General, Grant entered the 1868 campaign

season with increased popularity among the Radical Republicans following

his abandonment of Johnson over the Secretary of War dispute. The

Republicans chose Grant as their presidential candidate on the first

ballot at the 1868 Republican National Convention in Chicago.[c] In his letter of acceptance to the party, Grant concluded with "Let us have peace", which became his campaign slogan.[173] For vice president, the delegates nominated House Speaker Schuyler Colfax. Grant's 1862 General Order No. 11 became an issue during the presidential campaign;

he sought to distance himself from the order, saying "I have no

prejudice against sect or race, but want each individual to be judged by

his own merit."[174] As President, Grant would atone for 1862's expulsion of the Jews. Historian Jonathan Sarna

argues that Grant became one of the greatest friends of Jews in

American history, meeting with them often and appointing them to high

office. He was the first president to condemn atrocities against Jews in

Europe, thus putting human rights on the American diplomatic agenda.[175] As was expected at the time, Grant returned to his home state[d] and left the active campaigning and speaking on his behalf to his campaign manager William E. Chandler and others.[178] The Republican campaign focused on continuing Reconstruction and restoring the public credit. [179]

1868 electoral vote results

Presidency (1869–77)

Main article: Presidency of Ulysses S. Grant

The First Family: Ulysses and Julia Grant's family at the "summer capital" in Long Branch, New Jersey, 1870

Grant selected several non-politicians to his cabinet, including Adolph E. Borie and Alexander Turney Stewart, with limited success. Borie served briefly as Secretary of the Navy, later replaced by George M. Robeson, while Stewart was prevented from becoming Secretary of the Treasury by a 1789 statute that barred businessmen from the position (Senators Charles Sumner and Roscoe Conkling opposed amending the law.)[191] In place of Stewart, Grant appointed Massachusetts Representative George S. Boutwell, a radical, as Treasury Secretary. His other cabinet appointments—Jacob D. Cox (Interior), John Creswell (Postmaster General), and Ebenezer Rockwood Hoar (Attorney General)—were well-received and uncontroversial.[192] Grant also appointed four Justices to the Supreme Court: William Strong, Joseph P. Bradley, Ward Hunt and Chief Justice Morrison Waite.[193] Hunt voted to uphold Reconstruction laws while Waite and Bradley did much to undermine them.

ليست هناك تعليقات:

إرسال تعليق